Key takeaways

- Cloud Migration and Cloud Exit are not opposing strategies – they are both part of the same Digital Transformation Lifecycle. Companies must explore each decision as context-dependent instead of trend-driven.

- Real-world Cloud Exit Cost Modeling should include more than monthly cloud bills. Staffing changes, parallel operations, transition periods, and potential applications retirement affect the real ROI of cloud, on-premises or hybrid strategies.

- The financial turning point, where repatriating workloads becomes cheaper than keeping them in the cloud, can be calculated. But only when companies include hidden costs such as dual infrastructure support during a transition period, CapEx investment, cloud backup retention and many others.

- Startups benefit most from public cloud flexibility, but large enterprises often reach a scale where repatriation provides better long-term cost control and internal efficiency.

- Cloud exit is not a rollback to legacy systems. It’s an optimization strategy. When done with clear planning, it can reduce expenses, simplify architecture, and align infrastructure with business priorities.

Introduction

In contrast, if the same startup goes on-premise infrastructure, it usually needs 1-2 IT generalists to manage backups, networking, and devices. That’s ~K/year in staff cost and K in infrastructure. Add in security and compliance (often more complex and manual in on-premise setups), and total costs rise to 0–225K per year. Bottom line for most startups is the cloud is not just simpler, it’s cheaper.

In the next sections, I will walk through financial models, key cost signals, and clear calculations that show the real return on investment of both staying in the cloud, and leaving it.

In the end, this is not a cloud vs. server debate. It’s a strategy question. And the companies that answer it with clarity and confidence will lead the next phase, whether that’s deeper cloud investment, hybrid optimization, or smart repatriation.

The lack of clarity around Cloud Exit ROI

Enterprise (2,000+ employees)

To calculate the true turning point, we now add two more factors:

Each of these companies has different cloud usage patterns and internal capabilities. But they all follow the same core logic when modeling TCO:

Cloud Migration and Cloud Exit Statistics

Where those lines cross, that’s the Repatriation Point. It’s not a fixed year. It depends on your workloads, staffing model, and ability to govern cost.

In the cloud, the same company might reduce IT headcount by ~30%, shift more responsibility to the CSP, and hire 8–10 cloud-savvy staff for IAM, DevOps, and FinOps. That’s about 0K/year. With infrastructure costs rising to ~4K (again factoring the cloud premium) and compliance falling to 7K (due to managed services and automation), total cost drops to .23M. That’s around 0K/year in savings, if managed well.

But things change at enterprise scale. A company with 2,000+ employees may already have 30–40 on-premise engineers and system admins, costing ~.4M/year. They run their own data centers, sometimes with thousands of servers. Their annual infra and compliance cost sits around .8M to .0M.

Cloud migration was never just about technology. It was about speed, flexibility, and getting ahead. But now that most companies are already in the cloud, the question has changed. It’s no longer “Should we move?”, but “Should we stay?”

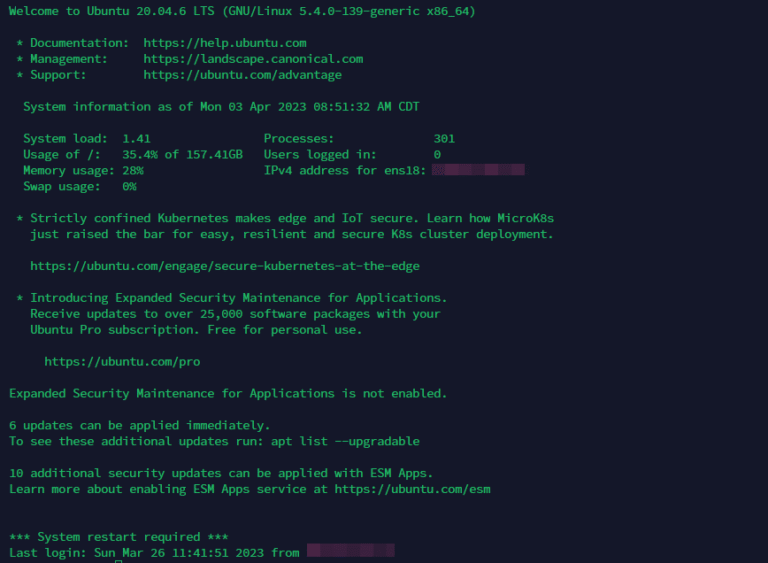

Today, nearly every company is in the cloud, at least partly. Around 96% of businesses globally now use some form of public cloud services, and 84% have adopted private cloud environments as well. These numbers show how deeply cloud technologies have become part of modern IT. But at the same time, another trend is emerging that can no longer be ignored – Cloud Exit.

So what exactly do we factor into this turning point calculation?

From my own experience, I can confirm this shift. The story I have seen again and again is not “cloud vs. no cloud,” but rather “cloud where it works, and alternative solutions where it doesn’t.” For any company managing at scale, especially with legacy systems or strict compliance requirements, hybrid and multi-cloud models are becoming the practical middle ground. But the key factor behind these decisions is almost always financial.

Typical examples of companies for calculation of Cloud Exit ROI

This article is my attempt to bring clarity to this subject. I want to explore what really happens when companies choose the cloud, or choose to leave it. Not in theory, but in numbers. I will show the financial impact of these decisions based on real-world examples and patterns I’ve seen across different business sizes – startups, middle-sized companies, and large enterprises. Because depending on where your company is in its growth, the cost balance can changed dramatically.

The goal of this cost model is to give decision makers a clear, grounded framework. Not just for “staying in the cloud” or “leaving the cloud”, but for building a strategy that supports scale, reduces waste, and aligns with long-term priorities.

Understanding these statistics helps bring realism into the conversation. Cloud migration is not just a one-way street. Cloud Exit is part of the bigger picture. And for many companies, it may be the only one way to return control of budgets and align infrastructure with long-term business goals.

What this shows is the hidden complexity of scaling cloud operations. Cloud does save time on hardware, but adds new financial layers. Governance, security, billing management, cost control – all these roles didn’t exist before, and now they’re critical. And if you lose visibility or control, the cloud bill becomes just another data center, but without the budget borders.

Conclusion: Cloud is financially effective if governance is strong and workloads are elastic. But watch out for cloud creep and staff duplication.

For this analysis, I use three common company sizes – a startup (around 25 employees), a middle-size company (about 300 people), and a large enterprise (2,000+ employees). These categories help us build practical financial models that reflect the most common real-world IT environments – from solo generalists to large teams with dedicated cloud governance and compliance staff.

If you plot these costs over time, you’ll see two lines:

Conclusion: The turning point has arrived. Cloud TCO now exceeds on-premise. Cloud Exit, at least partial, is worth serious evaluation.

But for many large enterprises, that point has already passed.

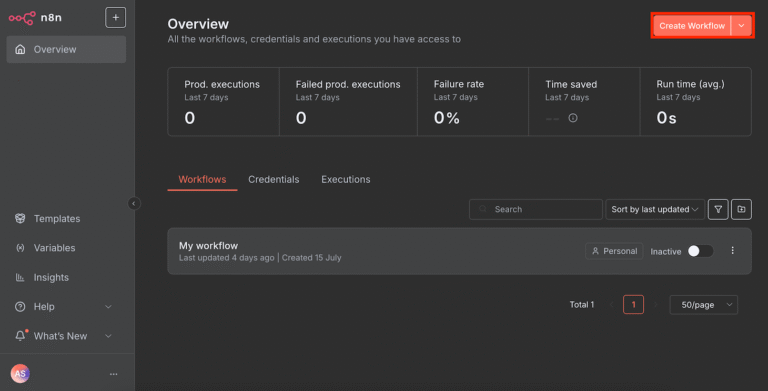

Over the last decade, I’ve led many IT transformations – some moving IT systems into the Cloud, and others moving them back out. During this time, I noticed two strong and opposite trends rising side by side – Cloud Migration and Cloud Exit. These directions may seem like contradictions, but both are growing. And both have real financial consequences that are often misunderstood or oversimplified.

Cost Modeling: How to Calculate the Turning Point

Across company sizes, the signals are similar. Smaller businesses often exit the cloud when pricing models turn out more expensive than planned. For middle-sized and large enterprises, Cloud Exit tends to come as a result of strategic reassessment. In both cases, repatriation is not about abandoning the cloud entirely, it’s mostly about choosing where the cloud still makes financial and technical sense.

The goal isn’t to be trendy. The goal is to be sustainable.

Now look at a middle-sized company with 300 employees. They typically have a mixed environment – some SaaS, some on-premise servers, and a growing cloud footprint. An on-premise model would require around 15 IT staff (~0K/year), plus ~0K in infrastructure and another 7K for compliance, audits, and tooling. That adds up to over .5M per year.

Let’s start with cloud adoption. For startups and smaller businesses (under 1,000 employees), cloud usage is very high. About 63% of their workloads and 62% of their data now placed in public cloud environments. For middle-sized companies (between 1,000 and 2,500 employees), around 41% are still in the process of planning or evaluating their cloud strategies. And among large enterprises, more than half are doing the same. In short, cloud migration is still active across all segments, but the rate of new adoption is slowing, and the focus is shifting toward optimization.

- IT Staff Costs – number of engineers, ops, cloud roles, platform support

- Infrastructure Costs – cloud services or on-premise servers + licenses (please remember, cloud infrastructure is on average 30% more expensive due to vendor margin and scaling overhead)

- Compliance & Security Costs – certifications, audits, governance

- Overhead – management effort, HR, procurement, budgeting

To understand the real ROI of a Cloud Exit, we need to move away from general opinions and look at real numbers. And to do that properly, we need to define typical company profiles, because a startup doesn’t think like a bank, and a 300-person company faces different risks than a 2,000-person enterprise.

- Cloud Exit Team – a project team dedicated to analysis, strategy, and execution

- Parallel Operations – because infrastructure won’t migrate all at once. For a period of time, companies must run both cloud and on-prem environments.

To answer this, we need a full model, not just infrastructure costs, but the real-world expenses that appear during a transition. Because Cloud Exit is not free. And it’s not instant. It takes time, people, and parallel infrastructure support.

Let’s start with the startup. In a cloud-first setup, they often outsource infrastructure tasks or delegate them to a DevOps engineer or full stack engineer. On average, this means less than one full-time person managing infrastructure. They may use a mix of SaaS tools and basic IaaS for development or analytics. Their annual cloud staffing cost is roughly K, and infrastructure costs add another ~.5K (with cloud’s typical +30% pricing premium). Compliance and security (ISO, SOC2, PCI DSS, GDPR, etc.) adds ~.5K per year, if needed. This brings the total annual TCO to around 0K.

- On-Prem TCO (5y): $1.025M

- Cloud TCO (5y): $800K

- Cloud Exit Team: +$260K

- Final Cloud TCO (with project): $1.06M

- Difference: On-prem is still ~$35K cheaper, but not significantly

Startup (25 employees)

By Oleksiy Pototskyy

- On-Prem TCO (5y): $7.985M

- Cloud TCO (5y): $6.155M

- Cloud Exit Team: +$370K

- Final Cloud TCO: $6.525M

- Difference: Cloud still saves ~$1.46M over 5 years

What I’ve shared here is not a one-size-fits-all answer. Instead, it’s a practical way to think about your own turning point, the moment when the cloud becomes more cost than benefit, or when repatriation starts to make sense. It’s a financial perspective, built on real numbers and real patterns, I’ve seen in this field for over a decade.

Conclusion: Cloud remains cost-efficient and flexible. Cloud Exit unlikely unless driven by other strategic goals.

- On-Prem TCO (5y): $30.5M

- Cloud TCO (5y): $33.4M

- Minus 20% Infra Retirement: −$2.6M

- Plus Exit Team: +$975K

- Final Adjusted Cloud TCO: $31.775M

- Difference: On-prem becomes ~$1.275M cheaper

So when evaluating Cloud Exit, don’t just compare server costs. Compare staffing models. Compare compliance workloads. Compare the complexity of cost visibility. Use your own numbers, your own organization chart, and your own needs, and ask where your turning point lies. For some, the cloud will still make perfect sense. For others, it may be time to step back, recalculate, and exit the cloud where it no longer adds value.

This isn’t about one model being “better” than the other. It’s about understanding your context, your size, your growth stage, your operational goals, and applying the right financial lens.

- Cloud Migration or Exit Team: Typical 2-year cost ranges from $200K (startup) to $975K (enterprise). This covers strategy, architecture, compliance, and execution across phases.

- Parallel Workload Support: During repatriation, engineers must maintain both environments. This creates temporary staff duplication and higher support load.

- CapEx Resurgence: Moving out of the cloud requires buying or upgrading hardware, provisioning data center racks, and restoring backup infrastructure.

- Retirement Potential: On average, 20% of workloads don’t need to be migrated. They’re legacy, duplicated, or obsolete. This is a powerful cost-saving opportunity, but only if properly identified during the planning phase.

- Compliance Shift: While cloud offers shared-responsibility models, on-premise requires direct investment in ISO, SOC, and GDPR tooling again. These costs rise, but so does control.

Startups still benefit the most from cloud – lower upfront costs, fewer infra roles, and maximum flexibility. Mid-size companies can also win, especially when workloads are elastic and FinOps discipline is in place. But for large enterprises, the financial mathematic gets more complex. When you factor in migration costs, parallel operations, and the chance to retire unused apps, the balance often shifts back toward on-premise, or at least toward a hybrid model with tighter control.

- Cloud TCO continues to rise, driven by premium pricing and staffing.

- On-Premise TCO has a higher upfront cost, but grows more slowly over time.

Repatriation, or Cloud Exit, doesn’t mean “going back in time.” It means rethinking. It’s a chance to ask – which workloads are still right for the cloud, and which would be more efficient on-premise or in a hybrid model?

Now, here’s where things get interesting. In parallel with rising adoption, a significant portion of companies are moving workloads back out of the cloud. According to recent U.S. data, 42% of companies have already repatriated at least part of their workloads, or plan to do so in the near future. And this isn’t a one-time anomaly. In past IDC surveys, up to 80% of companies reported some form of workload repatriation within a single year. The trend is real, and growing.

Why now? Because for many businesses, cloud bills are becoming harder to predict and harder to justify. The pricing model of cloud services can feel flexible at first – pay for what you use, scale as you grow. But over time, if not managed tightly, these costs often grow faster than expected. Especially when no one is clearly responsible for tracking the budget, and resources are may quickly and unpredictable grow just to meet delivery deadlines.

Let’s look at the real numbers over a 5-year horizon:

Conclusion

Middle-Size Company (300 employees)

In theory, the cloud removes physical infra needs. But in reality, these savings are offset by new roles – FinOps teams, platform engineers, cloud architects, compliance auditors, and security specialists. Staffing costs rise to M/year, infra to .6M (before egress and optimization), and compliance to ~.08M. All together, the cloud model for a large enterprise can hit .6M or more annually, often exceeding the cost of well-managed on-premise setups.

What drives this reversal? The top two reasons are cost and security. About 43% of IT leaders say their cloud costs ended up higher than expected. Many only realized this after implementation, when monthly bills started to exceed budgets. Another 33% pointed to security and compliance concerns, areas where some organizations feel more control when managing infrastructure directly.

My goal here is not to sell you one model over another. I want to help decision-makers understand both Cloud-First and Cloud Exit strategies from a financial standpoint. The technical part is important, but in this article, I will focus only on the money – the return on investment (ROI), the long-term cost models, and how to measure whether your current path still makes financial sense.

If you’re a decision maker, here’s my advice:

- Start with visibility – know your infrastructure costs, your team load, your workload patterns.

- Don’t guess – build a cost model across a 3- to 5-year horizon.

- Include transition costs, staffing changes, compliance impact, and expected savings from applications retirement.

- Use your own numbers, not vendor estimates.

- And most of all, don’t treat cloud exit as failure. It’s evolution.

Let’s walk through what this looks like in practice, using the same three company types – startup (25 people), middle-size company (300 people), and enterprise (2,000 people).

This doesn’t mean cloud is “bad.” It means we have matured. Cloud is a tool. And like every tool, it needs to be reassessed as the context changes.

Once we’ve seen the total yearly cost of cloud vs. on-premise across different company sizes, the next natural question is – where exactly is the turning point? That moment when the cloud stops being the most cost-effective option, and a partial or full Cloud Exit starts to make sense.