Four and a half hours later, the agent had produced a working HTML5 parser. It passed over 9,200 tests from the official html5lib-tests suite.

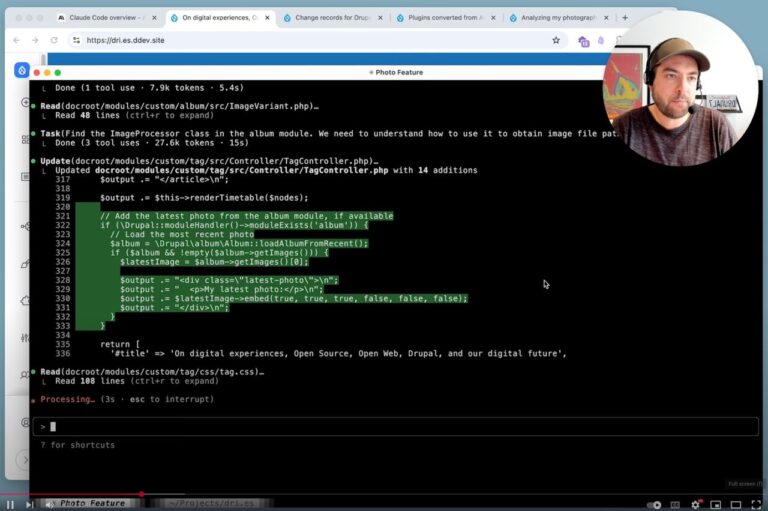

Geoffrey Huntley’s Ralph Wiggum loop is probably the cleanest expression of this idea I’ve seen, and it’s becoming more popular quickly. In his demonstration video, he describes creating specifications through conversation with an AI agent, and letting the loop run. Each iteration starts fresh: the agent reads the specification, picks the most important remaining task, implements it, runs the tests. If they pass, it commits to Git and exits. The next iteration begins with empty context, reads the current state from disk, and picks up where the previous run left off.

Willison’s success criteria were “simple”: all 9,200 tests needed to pass. That is a lot of tests, but the agent got there. Clear success criteria made autonomy possible.

The boundary keeps moving fast. A year ago, I was wrestling with local LLMs to generate good alt-text for my photos. Today, AI agents build working HTML5 parsers while you watch a movie. It’s hard not to find that a little absurd. And hard not to be excited.

HTML5 parsing is notoriously complex, but the specification precisely defines how even malformed markup should be handled, with thousands of edge cases accumulated over years. The tests gave the AI agent constant grounding: each test run pulled it back to reality before errors could compound.

Cursor’s research on scaling agents confirms this is starting to work at enterprise scale. Their team explored what happens when hundreds of agents work concurrently on a single codebase for weeks. In one experiment, they built a web browser from scratch. Over a million lines of code across a thousand files, generated in a week. And the browser worked.

As Simon put it: “If you can reduce a problem to a robust test suite you can set a coding agent loop loose on it with a high degree of confidence that it will eventually succeed”. Ralph loops and Willison’s approach differ in structure, but both depend on tests as the source of truth.

Or maybe it is? An AI agent could evaluate a page against brand guidelines and return pass or fail. It could check reading level and even do some basic accessibility tests. The verifier doesn’t have to be a traditional test suite. It just has to provide clear feedback.

Of course, the Ralph Wiggum loop has limits. It works well when verification is unambiguous. A unit test returns pass or fail. But not all problems come with clear tests. And writing tests can be a lot of work.

Why? Because carrying everything with you all the time is a great way to stop getting anywhere. If you’re going to work on a problem for hundreds of iterations, things start to pile up. As tokens accumulate, the signal can get lost in noise. By flushing context between iterations and storing state in files, each run can start clean.

Humans are moving to where they set direction at the start and refine results at the end. AI handles everything in between.

If you think about it, that’s what human prompting already looks like: prompt, wait, review, prompt again. You’re shaping the code or text the way a potter shapes clay: push a little, spin the wheel, look, push again. The Ralph loop just automates the spinning, which makes much more ambitious tasks practical.

From solo loops to hundreds of agents running in parallel, the same pattern keeps emerging. It feels like something fundamental is crystallizing: autonomous AI is starting to work well when you can accurately define success upfront.

The title of this post comes from Geoffrey Huntley. He describes software as clay on the pottery wheel, and once you’ve worked this way, it’s hard to think about it any other way. As Huntley wrote: “If something isn’t right, you throw it back on the wheel and keep going”. That is exactly how it felt when I built my first Ralph Wiggum loop. Throw it back, refine it, spin again until it’s right.

All of this just exposes something we already intuitively understand: defining success is hard. Really hard. When people build pages manually, they often iterate until it “feels right”. They know what they want when they see it, but can’t always articulate it upfront. Or they hire experts who carry that judgment from years of experience. This is the part of the work that is hardest to automate. The craft is moving upstream, from implementation to specification and validation.

For example, I’ve been thinking about how such loops could work for Drupal, where non-technical users build pages. “Make this page more on-brand” isn’t a test you can run.

It sounds like a party trick. But it worked because the results were easy to check. The unit tests either pass or they don’t. The type checker either accepts the code or it doesn’t. In that kind of environment, the work can keep moving without much supervision.

The question for any task is becoming: can you tell, reliably, whether the result is getting better or worse? Where you can, the loop takes over. Where you can’t, your judgment still matters.

As I argued in AI flattens interfaces and deepens foundations, this changes where humans add value:

The key difference is how state is handled. When you work this way by hand, the whole conversation comes along for the ride. In the Ralph loop, each iteration starts clean.

A few weeks ago, Simon Willison started a coding agent, went to decorate a Christmas tree with his family, watched a movie, and came back to a working HTML5 parser.

That doesn’t mean it’s secure, fast, or something you’d ship. It just means it met the criteria they gave it. If you decide to check for security or performance, it will work toward that as well. But the pattern is what matters: clear tests, constant verification, and agents that know when they’re done.

Simon Willison’s port of an HTML5 library from Python to JavaScript showed the principle at larger scale. Using GPT-5.2 through Codex CLI with the --yolo flag for uninterrupted execution, he gave a handful of prompts and let it run while he decorated a Christmas tree with his family and watched a movie.