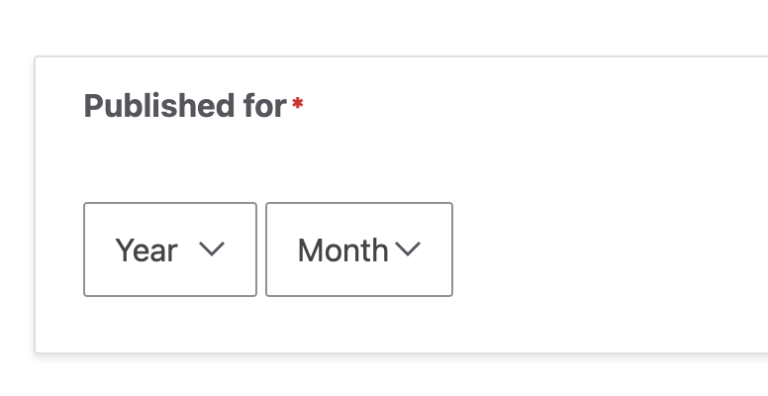

How to create a partial date field in Drupal (i.e. Year & Month without Day)

Follow these steps to change the date’s output for your frontend:Let’s get right to it: How to remove the time from a date field in Drupal How to hide the time Drupal’s frontend…